Buck Sargent's Warrior Politics

"Hopefully this Buck won't stop …

one of the best damn MilBloggers to ever knock sand from his boots." -- The Mudville Gazette

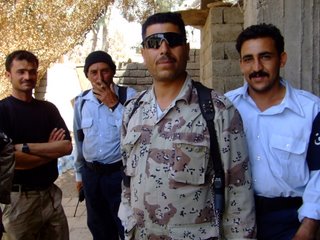

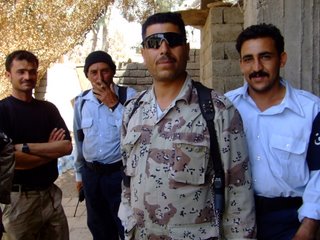

Iraqi Five-O, standing tall. Photo (and Oakleys) courtesy of Buck Sargent

Iraqi Five-O, standing tall. Photo (and Oakleys) courtesy of Buck Sargent

The bravest are surely those who have the clearest vision of what is before them, glory and danger alike, and yet notwithstanding, go out to meet it.

-Thucydides

There exists an underreported but ever-present crossover between war and crime that has taken hold in the past year throughout the large metropolitan areas of Iraq. It may always have been a factor, but it has become even more apparent over time. A deadly mix of organized criminality and jihadist savagery has increasingly come to blur the distinctions between the acts of violent terrorists and that of common thugs.

In some cases, the spoils of crime are used to fund terrorist activity. In others, attacks against Iraqi authorities and community leaders bear closer resemblance to gangland turf wars than any of the various ideological or religious themes propagated by the Al Qaeda-driven news cycle.

The typical cell structure of the insurgency can in many cases be likened to a series of disconnected Arab mafias. A tribal omerta of fathers, sons, brothers, and uncles may constitute the core of an insurgent cell and survive on criminal activity in between sporadic cash payments from committed jihadist leaders in return for attacking targets of opportunity. Whereas this opportunity once spelled U.S. and coalition forces, the bulls-eye later shifted to the indigenous army and police. This has been merely Darwinism at work, as all the brave-but-stupid arhabbi have since been reunited with their Prophet at 2,400 ft./sec. And those who remain are more savvy and less willing to stick their necks out. What good is easy money if you’re not around to spend it?

As the Iraqi Security Forces have improved, gaining in confidence, technical and tactical proficiency, and especially in numbers over the past year, the bulls-eye has jumped yet again. Civilians have become the new quarry, just as they have always been to any criminal element that preys on the weakest, most vulnerable, and least likely to fight back. Kidnappings of wealthy Iraqis (or their children) for ransom, as well as protection rackets -- mafia-like extortion of businesses under threat of harm -- have also become all too common.

This turn away from organized resistance and toward random violence for violence’s sake serves the interests of all the various groups who oppose a free Iraq. For the Saddamists who long to return to power and who will never recognize a freely elected government, it is a chance to make these officials appear weak and impotent. With a brutalized and fearful populace demanding protection from officials in Baghdad, one truck bomb outside a crowded mosque is all that’s necessary to shatter public confidence in representative democracy.

For Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia, it has finally sunk in that breaking the vise grip of the American military requires breaking the fickle will of the American people. To do this, the whole of Iraq need not be thrown into chaos, it only need appear to be so. In the AQ playbook, the war will be won or lost on CNN’s Headline News. The targets need not have any strategic value, they need only to bleed, explode, or catch fire.

As the violence recedes across the majority of the provinces in Iraq, so do the media goalposts for victory get pushed farther and further away. When the NY Times no longer finds Iraq newsworthy, you will know which side has won.

Our current enemies are following a script that is not .original. Following the surrender of Nazi Germany, die-hard Nazi guerrilla units terrorized and assassinated both local officials and civilians who cooperated with Allied occupation forces. We stayed the course then. We would be wise to do so now.

Accordingly, neither is violent instability a necessarily novel phenomenon unique to post-invasion Iraq. It may be a newly reported one, but ethnic and sectarian bloodletting came in a close second to soccer as the national pastime under the Baathist regime. The Nazis’ natural German efficiency had led them to catalog their horrific crimes with astounding precision. It remains to be seen whether the reams of captured Iraqi documents will reveal the same once they are eventually translated. Until then, we can only count the unearthed skulls and bear witness to those whose grief predates the recent American interest in their native land.

Mass graves stand as the ultimate “get tough on crime” position, with a recidivism rate that would shame even Saudi Arabia. Repressive tyrants like Saddam maintained power with the policy of “kill ‘em all and let Allah sort them out.” In any other context it would have been deemed genocide. In the since discarded “realist” approach to the Middle East, it was rationalized away as the necessary evil of a regional strongman, ruling with an iron fist over an unruly populace.

On the eve of the American incursion Saddam was said to have emptied his jails of up to 100,000 inmates, providing a lot of idle hands to suddenly unleash upon a devastated Third World economy (And in case you were wondering, Iraqis aren’t exactly big on midnight basketball.) In the Hobbesian Middle East, idle hands are the jihadi’s workshop.

For a new Iraq emerging from the darkness, this coalescence of violent insurgency and base criminality is a double-edged sword. Fighting it without destroying everyone and everything around it requires an increasing reliance on law enforcement tactics and all the restrictions that come with them, yet the criminals are utilizing terrorist weapons of war that make routine police work a militarily lethal business. With law enforcement comes legal protections, and with legal protections come judicial decisions that often err on the side of terrorists over troops and victimizers over victims.

No war can be adequately fought using law enforcement methods -- having to rely on admissible evidence and chain of custody and protections from coercive interrogation techniques. That we now find ourselves in this strange middle ground between war and peace is precisely the problem.

The respect for and protection of civil liberties is clearly important within a free society, especially such a fragile one on the brink of civilized adolescence like Iraq. Yet as Justice Robert Jackson once observed, a constitution is not a suicide pact. You won’t have a civilization to protect if anarchy is allowed to run rampant.

There are times when it appears we may have exported to the Iraqis some of the more onerous aspects of our system as well as the more enlightened ones; specifically the coddling of criminals. When initially briefed on all the necessary red tape that came with detaining and processing the bad guys before we deployed, the running joke of the company was “take no prisoners -- there’s less paperwork.”**(Relax, moonbats. This didn't involve the SecDef or an Executive Order. It was only a joke.)But the humor recedes when you come to find you're often dealing with a 50/50 chance of conviction in Iraqi courtrooms (at best). Not only do you have to worry about being shot at or blown up again next week, you have to worry about the exact same guy behind the trigger. Same time... same place... same guy.

This revolving door of catch and release is a common frustration among soldiers and Iraqi citizens alike. Nothing is more demoralizing than making a righteous snare of a known terrorist than the knowledge that he was promptly released by a Baghdad magistrate due to “lack of evidence” or an administrative snafu. Three weeks later he’s back on the streets planting bombs. The absurdity of it all forces troops in combat to often have to think and act more like Eliot Ness than Audie Murphy. (Has anyone thought to look into Zarqawi’s back taxes? I'm just putting that out there...)

Our unit had steeled itself for a brutal year-long experience; something along the lines of Tour of Duty. Yet the reality of what we experienced was closer to a bizarre mix of CSI, CHiPs, and Dragnet, with a nod to Iraqi Vice and Magnum, P.R. thrown in for good measure.

Sure, there were the midnight raids and hit & run attacks, the intermittent IEDs and too-close-for-comfort sniper fire. Over the previous nine months across the north of Iraq our brigade has suffered over 230 wounded and lost 14 soldiers -- 10 to hostile fire. But despite what you see on television, the following actions were far more commonplace:

Explosive residue testing. Crime scene photography. Eyewitness sworn statements. Evidence collection. Forensics "cleanup" (of Kentucky Fried Terrorists). Onsite lineups. Stake-outs, snitches, and sting operations. Electronic surveillance. Prisoner transport. Route overwatch. Counter-propaganda distribution. Get-out-the-vote drives. Vehicle checkpoints. Dismounted foot patrols. Curfew enforcement. Traffic direction. Ballot integrity escorts. Bootleg gasoline interdiction. If we could have found one, we may have even “raided” a speakeasy or two. Technically, it's still a war. Troops are still in contact, and the enemy is still out there. But one can't help but feel at times like a cop with just a really bad beat.* * *

A few months back, my platoon made a routine stop to one of the numerous Iraqi police stations in Mosul. Our mission: Retrieve a suspect accused of sniping American soldiers. As is custom in Iraq, several men appeared and began the “meet and greet” process with our LT and his entourage. They began glad-handing all the men present, ending with one nonchalantly standing beside them who our platoon leader didn’t recognize or pay much attention to. “Okay, now where’s my detainee?” he asked, not realizing that he had just shook hands with the terrorist they had come to collect.

Once we step back and allow the Iraqis to take the reins, the kid gloves that come packaged with our queasy western culture are going to have to come off if they are to be even remotely serious about stamping out the criminal underworld committed to destroying their country from within. They can‘t afford to play nice like Mr. Rogers; they’re going to have to think like Dirty Harry. Because anything less and they’ll all end up like Sonny Corleone.

Therein lies the rub: being able to defeat one’s enemies without becoming them. In the wake of Saddam Hussein, such an about face in the societal legal code from the foregone conclusion of guilt to the presumption of innocence is bound to have blowback. But the Faustian bargain made in every free society balances between the benefit of order and the benefit of the doubt.

It took over four years to bring Zacarias Moussaoui to justice through our own convoluted legal system, and considering the magnitude of the “criminal” plot he was convicted of being party to, significant doubt remains whether justice was truly done. Would it have been overly prejudicial to have screened United 93 for the jurors during the sentencing phase of the trial? Perhaps it would have reminded them that a “troubled childhood” cannot by itself come close to explaining away the very real presence of pure evil in the world. The question should not be Why do they hate us?, but What can be done -- what must be done -- to stop them?

As good a place to start as any would be to occasionally allow ourselves the benefit of the doubt. To let national secrets remain secret and refuse to succumb to conspiracy theory hysteria over hyperbolic security measures. To permit the military to adjudicate its own and refraining from pre-convicting them in the court of public opinion. And to allow our own elections and the very policies validated by them to stand, rather than consistently undermining them at every turn.

“America, you lose,” spat Moussaoui upon being denied his state sanctioned martyrdom injection. Due to our dumb luck, his role on that fateful day was averted; due to our legal intransigence, the overall cause he served was not. I don’t know about you, but I’d prefer terrorists tell it to the J-DAM than the judge.

But if we allow ourselves to revert to the pre-9/11 mentality of combating terrorism with indictments and subpoenas; if we fall back into feeble reaction over bold preemption; if we grant a trial to every illegal combatant held at Guantanamo Bay, secretly hoping they die of old age before our federal courts inevitably sentence them to time served and community service…

Then we have already lost.

COPYRIGHT 2006 BUCK SARGENT

Sgt. Clifton Sweet makes a new friend. Photo by Buck SargentAmerica is great not because of what she has done for herself, but because of what she has done for others.

Sgt. Clifton Sweet makes a new friend. Photo by Buck SargentAmerica is great not because of what she has done for herself, but because of what she has done for others.

-John McCain

AMERICAN SOLDIER SOUNDBOARD

A CONVERSATION WITH CAPTAIN JOHN TURNER

As the second highest ranking officer attached to our company, as well as the liaison between our platoons on the ground and the needs of the Iraqi people in our sector, Captain John Turner is in a unique position to offer his perspective on the Iraq War in general, the situation here in Mosul, and what the American public should know about their soldiers serving overseas.

After providing him with a series of written questions he graciously agreed to accommodate yours truly with his remarkably candid personal and professional insight on the battle for hearts and minds both at home and abroad.

Start of Interview

Describe a little about your background and what chain of events brought you to Iraq.I believe I am the product of America. I was raised in a middle class working family. I remember my father working overtime to pay for the sports my sisters and I participated in. I was a total mess as a teenager as I guess so many people are. I had no desire to study or had a lot of goals. I just wanted to have a good time and a little fun.I joined the Coast Guard at 17 for an opportunity to get out of the Midwest. I started out as an enlisted member of the Coast Guard in 1992. I left the service in 1996 to begin a college career. I say career because I was in school for so long. I graduated college and became a restaurant chain manager. The events of 9/11 encouraged me to once again rejoin the military.I completed my ROTC requirements in 2002 and started active duty in Jan 2003. I was completely aware from the time I accepted my commission I would probably be deployed to Iraq. I have great pride and feel that it is a honor to serve the U.S. as an officer in Iraq. Look at the things I have been able to accomplish: a college graduate, a commissioned officer, and a combat leader.America is the land of hope, and if defending that hope requires me to spend a year in Iraq, then I am proud to be here.Your training background is that of an artillery officer, yet your role in Iraq has instead focused on what the Army calls “information operations” (IO). Have you found it difficult to adapt to this new role thrust upon you?Artillery officers have the greatest view of the battlefield. We see the big picture of what commanders want and need in order to execute their mission. So IO falling on the shoulders of the artillery community is a natural fit. We have been developing plans based upon intent and effects as a profession for years.The challenges with IO are that every action that takes place on the battlefield affects what we do next. The battlefield in Iraq is ever changing and my capacity to understand IO increases everyday. IO has been a great challenge for me and one that keeps things exciting and busy.The goal of IO is to amass information to provide commanders the best advice on how to improve security and prosperity in their sector. The main mission to advise my commander is still there but my experience level was low in the beginning and that made it difficult to adapt. Experience always pays off and helps people make informed decisions.What changes have you witnessed in Mosul over the previous eight months? Has there been progress, or is the status quo simply being maintained?Mosul is a city of great hope and opportunity. The city has such a deep foundation in history and biblical times that it offers hope of a brighter tomorrow. The future in Iraq will be hospitality. Yes, I said hospitality in Iraq. The history here in the entire area from Israel to Saudi Arabia will lend itself to tourism when security is finally established.The Middle East is where civilization began and history continues to be made. The biggest misconception I had coming over here was the social aspect of the citizens. Being an American I understood hope, prosperity, and dreams. But the Iraqi people have known nothing but disappointment, fear, and brutality for years.For change to really occur in Mosul it must be more than cosmetic--it must be an ideological revolution. Not religious ideology, but for economic beliefs to change. Capitalism and freedom are things that we take for granted but are not the same to the Iraqi people we offer it to everyday.Offering freedom and hope to an Iraqi is like offering a porterhouse steak to a young adult raised in a vegan household--they have no idea what they are turning down. The table must be set to allow economic growth and personal wealth to be earned in order for the Iraqi people to succeed. These are things that their government must create and work with the world in order to develop a strong economy that produces wealth.The U.S. Army is preparing the Iraqi security forces to take the lead in policing the country and rely on the U.S. less and less. Here in Mosul, our battalion recently handed over responsibility for the majority of our sector and its battle space to the Iraqi army. Are they motivated enough to patrol the neighborhoods enough on their own and provide for the people’s security?Yes, in the past several months the security situation has improved in Mosul, and the Iraq Police and Army are providing this security for their people. There have also been two nationwide elections held to establish a ruling government supported by the people of Iraq. So the next step in building a strong Iraq with Mosul as the largest northernmost city is working. Time and patience will go a long way toward reforming the economic status from a socialist government that provided all services to a supply and demand market-based system.Every urban society has elements of violence--theft and robbery, kidnappings and murder. But crime and terrorism have different motivations. Do you believe the violent crime aspect is skewing the news coverage of the war? Would it be accurate to say that the insurgency has morphed into a loosely organized crime syndicate, a product more of inner city joblessness and the malaise of young Iraqi males than necessarily one of religious extremism?You can look at America and see urban battle zones in nearly every major city. Does this mean that America does not have opportunity or hope? No, but not everyone seeks to take advantage of these situations.Iraq is a political and media hotbed right now and has a lot of national attention. The media is in the information business and has limited time and space to report on events. The violence is easy to report and quick to cover so it all falls under "the insurgency." The insurgents get credit for murders and crime that they are not even involved with but probably do encourage because it helps their cause. But the insurgency is weakening and everyday some elements have probably shifted over to organized crime.Many of the problems and complaints across the city appear to be due to a notable lack of local government services that average Americans take for granted, such as reliable electricity, trash pickup, sewage infrastructure, street repair, etc. What will it take for Iraqis to start taking responsibility for their own cities and neighborhoods?They are taking responsibility for their own problems but it takes time. Security, security, security is the key to all improvements, and the challenge Iraq faces is the best way to increase this security. American can’t provide all the services. The Iraqis must in order for things to work, and brave men must step forward in order for that to happen. And they are.As the Iraqi Police and Army improve and provide security, so will local leadership who have Iraqis to partner with. The Iraqi Security Forces are the correct answer and are improving everyday.Mosul today is a changed city from the total collapse of order from 2004-2005, yet insurgent cells still are able to mount attacks on U.S. or Iraqi forces on an almost daily basis. Is there a command and control structure to the enemy operating within Mosul, or are they merely the work of out-of-work opportunists getting the most bucks for their bangs?The insurgency has been weakened in Mosul but still exists. The ISF are weakening them everyday, and as the local populace gains confidence in them the insurgency will be destroyed. The U.S. cannot eliminate it entirely but can only set the conditions for the Iraqi people to end the insurgent activities themselves. And we are doing a great job of enabling the Iraq People.To the best of your knowledge, what percentage of the enemy in Mosul is homegrown and what percentage are foreign jihadists hell bent on sowing chaos and instability?The activity is funded by people that do not want a strong democracy in the Middle East. Iraq was a strong power in the Middle East and some in the region probably never want Iraq to be powerful again, let alone a shining beacon of hope. The violence is not based on religious beliefs but fear of a strong democracy in the region. Building a strong and powerful nation is what we need to do in order to combat the jihadists, and Iraq will be that country one day.I can’t say what [percentage] is home grown and what is foreign, but I believe it is more politically than religiously motivated.The diverse population of Mosul is split predominantly among Sunni Arab and Kurdish Muslims, along with pockets of Assyrian and Chaldean Christians, Shia Muslims, Yazidis, and Turkomans. Have you witnessed any signs of sectarian conflict or what some believe could (or already has) escalated into full-on civil war?A revolution is indeed under way in Iraq, but not necessarily a violent one. The country is made up of many different sects and people, true. That is their strength: the history and culture of their own people. People want peace and prosperity in Iraq. The violence in Mosul is against change, not one particular sect of people. The insurgents do not want democracy and hope--they want power and control.So is an insurgency a war against the government? Yes. But not one simply pitting sect against sect. There is no ethnic cleansing going on in Mosul. Just tempered success and a lot of hope for a bright future.How successful has the predominantly Kurdish Iraqi Army in Mosul been at directing and interacting with the Arab population?I have personally seen the Iraqi Army leadership working with the local populace to improve security. There is a big misconception that they cannot get along--they can. The Kurds and Arabs alike want peace and harmony. Kurds and Arabs live in the same neighborhoods in Mosul successfully. So the Iraqi Army knows it is responsible for security in [all of] Mosul, not just security for the Kurds only.Author and foreign correspondent Robert Kaplan, whom you spoke with during his time here several months ago, made a point in his article The Coming Normalcy? for The Atlantic that insurgent activity has dropped "to the point where international journalists no longer consider Mosul an important part of the ongoing Iraq story." What is your take on this?That shows the success that has been accomplished in Mosul. When the media doesn't see any shiny objects to chase here anymore then things must be improving.Reconstruction is boring. Violence gets viewers, not rebuilding and reconstruction. The media is a business, not a public service. They report what sells, not what completes the story. Violence sells and rebuilding is boring, so why cover it? Look at the movies we watch -- they are full of violence. Name the last great movie made about rebuilding a society and its infrastructure.The American Army is bound by legal and humanitarian constraints in how we deal with and fight a lawless and inhumane enemy, concepts traditionally foreign to Iraqi police forces. How do we balance constraining their aggressive impulses with allowing them to be truly effective at rooting out an enemy that hides among the population?Easy, by setting the example. We’ve certainly set the standard for how to aggressively patrol while still leaving as light a footprint as possible. And the Iraqis have the distinct advantage of not having to fake their way through the cultural subtleties--they grew up with them. I suppose only time will tell how well they’ve internalized what we’ve tried to teach them.

As for the populace, what do you think it will take to create more employment opportunities for young Iraqi males who may be riding the fence between hard economic times and the easy money of the insurgency? Can Civil Affairs handle the workload of public works projects? Where is all the foreign investment? Where is the UN? How can we better contract Iraqis to rebuild their own country and imbibe them with a sense of ownership for their situation?Civil Affairs is working hard to establish a structure that allows the Iraqi government to improve meeting the needs of the Iraqis. The governmental structure is still being established and the local leaders are learning how to get things done.There are no easy answers for what we are supposed to be doing. Critics say the military leaders and politicians have made so many mistakes here that we can’t win. But the problems Iraq faces are the same [ones] that every country faces. The uneducated are not unintelligent, as think-tankers seem to believe.The motivation to be an insurgent is the same as any inner city drug dealer. Humans will survive and greedy power-hungry lunatics will take advantage of them. Like the teenagers selling cocaine in America, the insurgent leaders hire the poor and desperate people to conduct attacks. This way the leaders never get killed or caught. The motivation is survival, not fundamentalism. Security will establish legitimate jobs and insurgent activity will decrease. The more jobs we create the harder it is for insurgent leaders to recruit.Security and international investment will help rebuild Iraq and the cycle to peace begins with the investment. The U.S. soldiers will work to get the ball rolling, but where are all the liberals that hate us being here raising money to help rebuild the country and restore order?The fact is that Iraq is in need of serious infrastructure overhauls that Saddam never offered. Most rural villages have had poor, if any, water supply for years. The schools lack supplies, rooms, and teachers. Iraq can be rebuilt, but as long as only the U.S. forces are rebuilding it and finding contractors and developing leaders, it will take awhile. France, Germany -- where are you? They can knock us, but where is their answer?A simple rule in the army is that if you have a gripe you better have a better way of doing it. Soldiers will help develop the country but those who won’t come over here to help have no right to criticize us. The day they step foot in the city and walk the streets and see the children and go house to house looking for leaders -- then they can say how messed up we are.Let's switch topics for a moment. Something that has always impressed me about the U.S. military is how much responsibility is expected of and demonstrated by 25-year-old sergeants and lieutenants (whose civilian peers are often still living with their parents) deposited in a foreign land and given a complex mission against near impossible odds. The popular culture often lampoons them as failed dead enders who joined for lack of economic opportunities or prospects, but that hasn’t been my experience or impression in the least. What is your view of the young men and women we serve with?I have a lot of respect for those who walk the streets with me and pull security while we look for leaders and identify what needs to be done to improve the conditions. These "dead enders" are building a nation from ruins. The soldiers who serve America are not dead enders but great Americans that believe America must be defended.The real dead enders are getting stoned and not looking for ways to improve themselves. The military has long been a place to come begin a career and learn how to become a leader. Every sergeant was once a junior soldier and set goals to become an NCO. Do dead enders set goals? Do dead enders get up at 0600 everyday to go to work to defend their nation?The Army takes whomever comes through the door and creates great leaders. Maybe some with limited options join the military during peacetime to improve themselves, but the young Soldiers we lead today are prideful Americans who believe in something greater than themselves.Less than one percent of U.S. citizens presently wear the uniform of their nation’s military. Even less have served overseas in Afghanistan or Iraq. As such, is it any wonder that such a large segment of the public misunderstands and disapproves of the war? What implications, if any, do you foresee for the future of the country when it will nearly always be "someone else's" sons and daughters who volunteer to serve in harm’s way?The value of what it takes to defend our freedom decreases and makes us look vulnerable to the rest of the world. The good news is that there will always be amazing Americans that will answer their nation’s call and defend her in every generation.Many of the soldiers over here have not yet attended college because they’ve put personal agendas on hold to do something bigger than personal goals. Most soldiers want to go to college one day but put service in front of their education. Iraq will set them up for success when they do attend college.Conflict is difficult and causes stress and challenges for those involved in it. The challenge of a college course pales in comparison to what they do here daily, and when they do finally go to school they will succeed because of their experiences over here.Parents and family and friends with loved ones overseas worry, but have pride in knowing such a person. No one wants to lose a family member at 80, let alone in their twenties or thirties. But the lessons learned by those who served in Iraq will be valuable long after Iraq is a free and independent country. One cannot go through this experience and not learn a lot about themselves and the world.Public support for the troops appears stronger today than it has been since WWII, even though more Americans purport to believe in us rather than why we’re here. With so relatively few families affected personally by the sacrifices made in the War on Terror, do you think the nation’s gratitude is genuine or only surface deep?I have said and still believe that it is harder for the families to send us over here than it is for us to come. We know from moment to moment what we are doing. The families back home never know what is going on from day to day. We only have to worry about each other -- they have to worry about losing a son, daughter, brother, sister, husband, wife, mother, or father.I have received so much support that I believe the average American is truly grateful for our efforts in Iraq. But many can’t understand why someone would put something before themselves. That is why we are different -- we believe in a greater cause, not just selfish gain. The soldiers over here are part of the best their generation has to offer.The recruiting crunch is talked about a lot because parents think their child is too important to fight for freedom. They are grateful we are here serving and thankful their child is not. Should we worry about what someone that selfish really cares about? Is a country not worth fighting to preserve even worth living in? They need to be asking themselves these questions not mocking those that do. Thank God our forefathers believed in freedom over personal gain.The average American is not well informed as to why we are here. They do not see the successes we experience daily. The media only report on the tragedies that occur. The real story is so hard to get at because it can’t be summed up in three minutes. Who would watch a three-hour nightly update on all the things that take place daily in Iraq?[The public] sees the political infighting and what the media choose to cover and forms an opinion off of that. That is like watching five plays of a football game and believing you can understand who won without even seeing the score. Those who were so sure that Iraq was WMD-free and were willing to gamble with our national security need to meet me in Vegas!Public support is important because the more the insurgents believe we are not supported in this struggle and the closer we are to leaving, the more attacks we have to fight off which decreases security for all Iraqis. The lack of belief in the cause improves the enemy’s morale just as support for us increases ours.So if Americans really want to support us, they must support our mission.

End of Interview

"Public sentiment is everything," noted Lincoln in 1858, presaging the great American tragedy of civil war that would come to define his own Presidency. "With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed."

He has yet to be proven wrong.

Special thanks to Cpt. Turner for sacrificing his personal time to indulge American Citizen Soldier and its readership with his views.

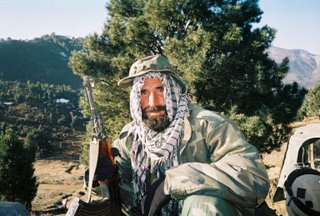

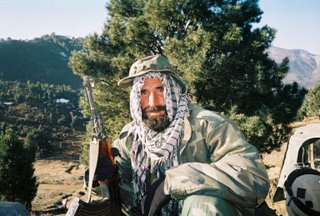

Silent Hassan: Afghanistan's International Man of MysteryPhoto by Buck SargentAMERICAN CITIZEN SOLDIER *EXTRA* This is the continuation of a series of selected excerpts from my Afghanistan war journal hand-recorded from October 2003 to August 2004. All OEB entries are previously unpublished.

Silent Hassan: Afghanistan's International Man of MysteryPhoto by Buck SargentAMERICAN CITIZEN SOLDIER *EXTRA* This is the continuation of a series of selected excerpts from my Afghanistan war journal hand-recorded from October 2003 to August 2004. All OEB entries are previously unpublished.

We do not differentiate between those dressed in military uniforms and civilians.

-Osama bin Laden

Tuesday 09March2004

Southeastern Afghanistan

Dare to navigate through the Army mine fields of Acronym Alley with a rare behind-the-scenes glimpse of some real-world military mission planning and execution:

2nd Platoon OPORD (Operations Order)

Company Mission: C company, TF (Task Force) 1-501st disrupts ACM (anti-coalition militia, aka Taliban/al-Qaeda) in OBJ (objective) Chestnut commencing 09MAR04, IOT (in order to) deny enemy safe haven and freedom of maneuver.

Purpose: The purpose of this operation is to demonstrate a presence throughout OBJ Chestnut, forcing the enemy to reposition his force locations. Our goal is to develop HUMINT (human intelligence) contacts that will provide timely intel on ACM in the area.

Key Tasks: Mounted reconnaissance, village assessment, cordon and search, VCPs (vehicle checkpoints), identify UXO (unexploded ordnance) for destruction by EOD (Explosive Ordnance Disposal), destroy/capture ACM forces/supporters, develop contacts within target villages.

Desired End State: ACM sanctuary and freedom of maneuver are denied. We maintain the ability to find, fix, and finish enemy forces in OBJ Chestnut.

Enemy Forces: ACM have begun their Spring Offensive and have increased overall activity in AO (area of operations) Geronimo. During the next few months, ACM will continue to increasingly conduct ops against ITGA (international government agencies) and possibly U.S. forces in Khost province. These attacks will attempt to show the local population that Taliban/AQ forces are still prevalent in Afghanistan, IOT decrease popular support of the coming local elections. These elections, to be held in June, will have major impacts toward the future stability of Afghanistan. The Taliban must destabilize this election process IOT maintain a foothold on their influence and sanctuary in the country.

Key Personalities: ACM forces affecting the Khost region are commanded by Jallaludin Haqqani. His main subcommander is Malem Jan, who during the time of the Taliban was Chief of the Secret Police in Khost. He is notorious for his involvement in over 300 disappearances in Khost as well as his noted affinity for young Pashtun boys. He works closely with a man named Darim Sedgai, who has explosives expertise. These two ACM leaders or personnel associated with them drive around in a black Toyota Landcruiser with license plate # 1129 and a red Toyota Hilux with license # 3195.

Another Haqqani subcommander is his son Siraj Haqqani, known to stay in Bangidar, Pakistan during attacks that he has launched. Bangidar is approximately 4-5 km east of BCP* 3 (border checkpoint). Satimi Jan, of tribe and village Sori Khel, was arrested six months ago but Afghan police released him for a reported large sum bribe from the elder Haqqani. Owns a white Toyota Corolla station wagon with red interior given to him by Haqqani. Responsible for transporting IEDs from Pakistan, emplacing them in Khost province, and attacking Jingle trucks that transport U.S. supplies between Gardez and Khost cities.

*Mountainous outposts that divide key traffic routes between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

His brother Haji Alam Jan was recently detained and released by TF 1-501. Haji Alam Jan said Satimi lives near Peshawar, Pakistan. Satimi is approximately 5’7”, heavy set with black hair and long black beard, and is a heavy smoker. We conducted a hard search of his village on 15JAN04 and detained his brother and two other villagers. They were all released on 20JAN04. In his compound was a book that identified about 140 ACM operatives by rank and unit.

In a 10JAN04 report a contact stated that Satimi was planting IEDs and planning with others to emplace IEDs against U.S. forces and/or AMF (Afghan Militia Forces). Participated in the stopping of transport trucks headed for FOB (Forward Operating Base) Salerno. Also stated that Satimi planned the 20DEC03 IED that killed two AMF personnel.

Haji Malem Khan: Main operational cell leader of attacks in the Haqqani area of influence along the Khost-Gardez road. He has been detained in Pakistan, but a contact informs us that he has been released on the sum of 1.3 million Pakistani rupees.

Kalam Gul: We received info on this individual from a new but reliable source. Our CA (Civil Affairs) officer met with him during a visit to the Gardez Selay markets. He claimed to be an OGA* (other government agencies) informant and gave us intel on Satimi and Kalam Gul, matching info that ODA** (Special Forces) sources at CAF (Chapman Air Field) have given. The source escorted our CA team to the homes of both Satimi and Kalam Gul. Source overheard Kalam Gul’s brother say that Gul has likely gone to stay with relatives in Khost and would likely stay there now that we know where he lives.

*Spookspeak for "CIA"

**Operational Detachment Alpha, military jargon for an SF (Special Forces) team

End OPORD

Okay, so that’s the official Army hooah-hooah high-speed Ranger version of what we do around here. Now allow me to provide the boots-on-the-ground low-speed Joe Snuffy reality of how things actually go on missions such as this one:

Tuesday morning we woke up at the ass crack of dawn for the aforementioned three-day mission to the high mountains of the Pakistan border region far to the southeast. The convoy was enormous, approximately 35 vehicles strong (so long, in fact, the lead Humvees were practically outside of Khost before the trail vehicle had even left the gate. Bin Laden could probably have spotted the giant dust cloud through binos from his mountain retreat).

The chow tents opened up several hours early just for us, so that we could get some food (or so-called food) in our bellies before we left. I’m sure the cooks love waking up early for us. It really shows in the quality of these pre-mission breakfasts. IHORE (International House of Runny Eggs).

Wouldn’t you know, I became violently ill about two hours into our ascent to 8000 feet, puking myself dry up on a hilltop while on a brief security halt. My stomach churning like Mount St. Helens, the sudden gastrointestinal upheavals left me so dehydrated I could barely stand on two feet. Doc Edmundson, our platoon medic, got me down to our Humvee and began to prep my left arm for a routine IV, yet I was already so incoherent I nearly tumbled right off the side of the truck from the sitting position. (All this I was told later; my own recollection is still a bit hazy).

I soon was laid out and stretchered into the back of the trailing FLA (medical vehicle) so that the convoy could continue on. There I spent the rest of the journey effectively comatose until I was rudely awakened by the decidedly unwelcome sensation of the PA (physician’s assistant) shoving something cold and hard “in through the out door.” (Our PA is notorious throughout the ranks of the 501st for this anal diagnosing fetish that apparently knows no bounds. Tales abound of soldiers having been disconcertingly “probed” for everything from sore throats to sprained ankles). Rather than allow him time to dream up other unnatural methods of taking my core temperature (or more things to shove up my rear besides thermometers), I quickly came to my senses and decided I felt much better, thank you. At some point I recall him asking me if I’d ever had kidney stones. Can I go now, please?

Eager to rejoin my squad at the front lines rather than hang with the First Sergeant and his merry band of bitch boys in the rear with the gear, I soon hopped the first Humvee back to their position overwatching a valley for enemy traffic. Apparently, while I was zonked out in the back of the FLA our convoy had done nothing but drive all day, eventually ascending to a near nosebleed altitude.

3rd Squad (with an attached gun team) spent the night in an observation position on a remote mountaintop, utilizing thermal scopes and alternating sleep shifts in a routine guard rotation. Few things are more miserable than standing watch over a featureless moonscape while wearing NODs (night vision goggles), freezing your testicles off, and struggling desperately to stay awake and remain alert. However, one such thing that qualified was barfing uncontrollably while on my hands and knees for the second time that day, dry heaving until my abs hurt. Apparently, the PA’s brilliant diagnosis of “dehydrated exhaustion” wasn’t quite so proctologically astute. Something was seriously amiss in the depths of my bowels, and it wasn’t about to go quietly. I still don’t know what it was -- food poisoning, stomach virus, the biohazardous state of the putrid Afghan air -- but I mercifully slept like a stone for the rest of the night, even through another by-now requisite enemy rocket attack from an adjacent hilltop.

Wednesday 10March2004

We ascended even higher to just over 9000 feet, which doesn’t seem all that remarkable until you attempt to walk up even a tiny hill and find yourself panting like you’ve just climbed Everest. The air is thankfully cleaner, yet noticeably thinner.

Most of the day was again spent riding up the narrow mountain switchbacks, the majority of us severely fatigued from the deathgrip required to stay balanced on the rear of the Humvees as we catapulted across the steep, uneven terrain. This activity was broken up by the occasional “presence patrol,” humping it on foot along the woodsy, snow-covered hills looking for God-knows-what. The only other living things up here are the ubiquitous pine trees (making it look much more like our Alaskan home than the Middle East), and the random Afghan shepherd guiding his herd. (It’s now become apparent to us that nothing deters these guys). The op order for this mission called for “village assessments,” yet we haven’t even seen more than two people the whole time we’ve been up here. As the Senator from New York might say, “It takes a village…to do a village assessment.”

Someone high up the chain of command brilliantly decided that we need to start “digging in” at night on these missions to guard against enemy indirect fire on rocket attack while we sleep. Never mind that in the four months we’ve been here already we’ve never bothered to do this before. If there is anything an infantry soldier dislikes more than digging foxholes (aka fighting positions or Ranger graves) with an 18” collapsible E-tool, I couldn’t at the moment tell you what it is. (But given more time, I’m sure I could come up with something).

But once darkness fell and our holes were dug, the PL sent our squad on a wild goat chase…er, I mean, mission… to check out a known nearby cave for possible enemy personnel seeking refuge. We were also directed to take “Crazy Ivan” (our green plastic silhouette target mascot that we’d bungee’d to the grill of our Humvee) and start a huge bonfire next to him in a lame attempt to invite contact and thus affix and pound potential ACM positions with indirect mortar fire.

No dice. No one fell for it. Crazy Ivan enjoyed a warm campfire all to himself that night, while the rest of us shivered in our Ranger graves.

Thursday 11March2004

The third day of a three-day mission is always the best one, because everyone is anxious to get back to the FOB. Nothing like a few days in the field to make us appreciate the creature comforts (i.e., only comfortable for a creature) of tent city Salerno.

This marks the first day I’ve actually been able to keep any solid food down other than my patented “PB&J IVs” (peanut butter & jelly packets squeezed directly into my mouth in one straight shot). Our long convoy descended the Haji Alps and rather than head back to camp like we’re scheduled to, the decision was made to finally find some villages to “assess.” We were all thrilled, of course. You know mission cycle is getting old when you’re anxious to go back on FOB security again.

One village near the border had an interesting twist: nearly all the males of fighting age (which in Afghanistan pretty much translates to “has learned to walk”) are over in Pakistan warring with another village that disputes their claim to their land. Personally, I thought we should go assist them with their tribal feud for the remainder of the day. I figured for them it would be like getting into a scrap with schoolyard bullies and having Stone Cold Steve Austin suddenly arrive to bail you out. If nothing else, it would have been good for some quality entertainment. But that’s probably as good a reason as any for not putting me in charge of anything.

Our route home was, as usual, yet another miserable dust-swallowing and tailbone-bruising ride from hell. Of course, someone had to go and mention the dreaded “R” word (“Hey, well at least it isn’t raining”), which was just enough misguided optimism to drive the Rain Gods to distraction. Idiot!

The little haji kids’ new favorite pastime -- when they’re not preoccupied with pestering us for bottled water, spare pens, or “biscuits” (cookies) -- is to frantically blurt out “Osama! Osama!” at passing American convoys and then point to the houses directly behind them. This is incredibly exciting the first time you witness it, less so the fifth time in half a mile. (Yeah, ha ha, you filthy little bastards). Still, it wouldn’t surprise me if Bin Laden really was sitting with his feet propped up in the window of one of these roadside mud huts, sipping chai and laughing his ass off as we rumble on by, totally oblivious.

Each platoon usually travels with at least one terp or AMF soldier to assist us when we encounter locals during a patrol or mission. 3rd Squad’s token AMF guy this time around was an Afghan named Hassan who didn’t speak a word of English (or a word of anything the entire three days, come to think of it). Still, we came to adopt him as an honorary squad member of sorts, giving him socks and gloves for his bare extremities in the frigid conditions (AMF soldiers are not exactly what you’d call “well paid.”) Traveling with the AMF and the terps has an added benefit: it seems to give us more clout with the locals when they see us riding side by side with a familiar bearded face, and provides us an air of legitimacy among the populace that we as yet another group in a long line of foreign invaders would not otherwise have.

Hassan especially seemed to enjoy the attention and notice that we received as we wound through the busy thoroughfares in “downtown” Khost, literally stopping traffic as onlookers would drop whatever they were doing (usually not much) to wave, shout, salute, give the thumb’s up, or chase us down the block. People jammed ten deep into passing taxis would crane their necks to gawk at us as is we were a presidential motorcade. We could even see burqa-clad women (if we looked closely enough) sneak peeks at us from behind their blue head-to-toe ninja veils. (Though orange and yellow burqas now appear to be all the rage in Khost. Take that, fascist Taliban fashionistas!)

Throughout it all, Hassan was waving and thinly smiling like the King of Kabul, or a celebrity hitting the red carpet for his latest blockbuster release. Albeit a scruffy-bearded, AK-sporting, really badly smelling one. Shirey finally got into the act as well, acknowledging the crowd from the truck turret with a raised heavy metal two-fisted devil salute. “Rock on!”

The ride back to the FOB Sweet FOB ultimately caked me with so much dirt and dust that I looked like I’d camoed up before we left. If there’s one thing I will never take for granted again in this world, it is the rare beauty of pavement.

COPYRIGHT 2006 BUCK SARGENT

- BUCK SARGENT

- United States

- Buck Sargent is the alter ego of a three-tour Iraq and Afghanistan veteran. He now enjoys sleeping late, not shaving, and being on the same continent as his wife and kids.

My profile