WHY ELECTIONS MATTER - TAKE I

Men make history and not the other way around. In periods where there is no leadership, society stands still. Progress occurs when courageous, skillful leaders seize the opportunity to change things for the better.

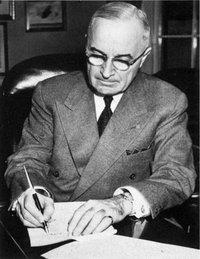

-Harry S. Truman

Elections do matter.

The following is the first in a four-part American Citizen Scholar series examining the influence and impact of presidential leadership (or lack thereof) in regard to U.S. foreign policy and its outcome during tumultuous periods in our nation's history.

In recent months, two Muslim nations have partaken in the voting process for the first time in their respective histories. Participation is high, the enthusiasm even higher; many brave death simply by registering or showing up at the polls.

By contrast, less than half of the eligible American voting public participates in our national elections every two to four years. It doesn’t matter who you vote for, say the pundits, critics, and cynics. Presidents and politicians are all the same.

When referring to such trivial domestic concerns as budgetary tug of war, the daily he said/she said of Capitol Hill carping, or the routine hitting below the Beltway -- perhaps the naysayers are correct. But when it comes to major foreign policy decisions that have wide ranging and long term consequences on the world stage -- history begs to differ.

This is precisely why elections matter.

THE TRUMAN SHOW

WHY ELECTIONS MATTER - PART I

How the Truman Doctrine Prescribed Containment for the Cold War and Trumped Communist Hegemony

President Harry S. Truman was a man who thought in plain and simple terms: black and white, right and wrong, good versus evil. And understandably so -- he lived in seemingly clear cut, straightforward times, where a man’s word was bond, and personal experience his ultimate guidepost. Unappreciated in his day, Truman was an old school Democrat who never flinched from the hard work and difficult choices of defending America, and whose bedrock political notions favored common sense over dollars and cents. "I never did give anybody hell," he said. "I just told the truth and they thought it was hell."

The War to End All Wars

At the ripe age of thirty three he volunteered to tackle the Germans in the bloody trenches of war-ravaged France. His eyesight was poor, to the degree that in order to enlist he was reduced to memorizing the army eye exam chart. By war’s end, however, he was not so nearsighted that he could not recognize the Allies’ grandiose folly of forcing round pegs of expectation into square holes of reality. The failure to exact an unconditional surrender -- coupled with a punitive peace treaty and a feckless League of Nations -- sowed the seeds of Nazism that would take root over the next two decades and ultimately lead Europe hurtling again toward war. As a newly-elected senator from Missouri, Truman would watch helplessly as Hitler’s aggression became emboldened by the western democracies’ refusal to stand up to him at Munich, and silently fumed as America remained mired in isolationism.

Despite being shut out of the halls of power as FDR’s third vice-president in four terms, he inherited the role of Commander-in-Chief in the final year of World War II. After only four months on the job -- barely seven of those in the executive branch -- he approved the coup de grace to the Japanese over Hiroshima and Nagasaki that would forever change the world. Ultimately taking lives in order to save them, it would unleash an atomic age in the process.

Civil Servant of the People

It was Harry Truman who -- in an election year, no less -- issued an executive order mandating the desegregation of the armed forces and the civil service; a hugely controversial move in the pre-Civil Rights America of 1948 that dumbfounded his supporters and ignited a firestorm among his critics. His explanation? It was the right thing to do. "We believe that all men are created equal because they are created in the image of God."

It was Truman who called the Korean Communists’ bluff as they deemed to take by force what they could not acquire through negotiation, laying American lives and stature on the line to protect the legitimacy of a new global institution unable or willing to do so itself. Following the recent loss of China to Communist takeover, the decision was a no-brainer, a requisite that succeeding presidents have not always met. Will Rogers called diplomacy "the art of saying 'Nice doggie' until you can find a rock." Give 'em Hell Harry took this to heart.

Truman pushed the Soviets out of Iran; came to the aid of Greece when their Communist surrogates threatened to overthrow it; and saved West Berlin by airlifting supplies in the face of a Red Army blockade. He was the first to recognize the infant state of Israel, the first -- and until recent events -- the only true representative government in the Middle East; "I had faith in Israel before it was established, I have in it now. I believe it has a glorious future before it - not just another sovereign nation, but as an embodiment of the great ideals of our civilization;" and presided over the Marshall Plan, the original blueprint for the proven feasibility of imposing democracy on a subjugated enemy. Modern-day cynics should take heed.

How We Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Truman’s enduring legacy, however, will remain his willingness to split hairs, not atoms; to engage international communism in a protracted war of competing ideas rather than a swift exchange of nuclear ordnance. Many scholars and critics have laid the blame for the Cold War’s gestation at Harry Truman’s feet, yet they fail to mention that the alternative could very well have meant another global war; only this time, one with the potential for unimaginable devastation. “I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought,” remarked Albert Einstein, “but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.”

As the Third Reich crumbled, the Soviet “Iron Curtain” descended across Europe, setting the stage for the final confrontation between East and West that fortunately would never come to fruition. Yet, if Soviet aggression was to be met, it would have to be met early with unambiguous resolve and steely determination to "support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures" — a sweeping ideal promulgated as the “Truman Doctrine.”

With its clarion call for dramatically increased defense spending, Truman’s directive would serve as the blueprint for U.S. resistance to any further Communist encroachment upon war-ravaged Europe and, to a lesser extent, the economically fragile East Asian Rim. In short, the U.S. was undertaking an essentially open-ended commitment, both military and economic, to defend freedom across the globe.

A Line in the Sand

Truman and his inner circle believed that an enduring peace could only be attained though demonstrative strength, based on the proposition that America—as the greatest independent democratic power—had moral, political, and ideological obligations to preserve free institutions throughout the world, and must equip itself with the military means to shoulder them. Consensus quickly formed that the Soviet Union would eventually hit a logjam if met with steady resistance when it sought to expand, a theory put forth by the State Department and Truman’s foreign policy inner circle. Put into practice, this strategy became known as “containment.”

Restraint of the Soviet menace would necessitate a massive buildup of forces not only to meet such a threat if it occurred, but also to discourage such belligerence in the first place. Extensive aid to the beleaguered nations of Western Europe and the Mediterranean would also be required if only to head off subversive elements within their own borders that could potentially spell disaster politically, if not militarily. Few within the State Department expected the Soviets to push for another costly war so soon after the last one, but none doubted that they would seek strategic advantage whenever possible, especially if the opposition was reluctant and the risks were minimal. It did not appear to most government analysts that war was likely; the Soviets simply did not seem strong enough yet to stage a war. However, that didn’t necessarily mean that they wouldn’t keep pushing their interests and pushing them hard, just short of war.

Career diplomats in the State Department cautioned to expect the Soviets to be extremely aggressive; to press and prod whenever they spotted weakness and opportunity. In order to beat the Soviets at this game, the West would have to vigorously contain the Soviets, which would probably engage the U.S. in a struggle that could last several decades or more. Though Truman tended to view the world as a struggle between democracy and totalitarianism, he feared that the steep tax hikes that his policies of containment called for could stall the economy, gut his domestic program, and potentially cripple his beloved Democratic Party. Since the end of the war, he had virtually dismantled the military and converted the nation back to a peacetime economy, planning to put more funds into healthcare and education. Yet, the hawkish Republicans in Congress were eager to pounce -- “soft on communism” their chief battle cry.

Confessions of a Reluctant Superpower

Americans by tradition were not keenly interested in foreign policy, and they certainly had little interest in maintaining the kind of gigantic military establishment that would be needed for containment. They remained deeply apprehensive about taking a lead role in world affairs, preferring to focus on all things domestic. And as they had after the First World War, they pressed Congress to demobilize quickly as soon as the war ended. In each case Congress had complied, cutting back on the military budget and ending the draft. President Truman needed to instill enough fear in Americans for them to approve of a gigantic new commitment to internationalism, a commitment totally at odds with the country’s deepest traditions: taking charge of the free world’s security, entailing huge financial costs and risking the transformation of the U.S. into a giant militaristic society. As he would later write: "A president either is constantly on top of events or, if he hesitates, events will soon be on top of him. I never felt that I could let up for a moment."

Containment jibed well with Truman’s innate sense of morality: it constituted the right thing to do and what needed to be done to bring it about. As an added benefit, upping defense expenditures so drastically offered him political cover on the conservative Right, and partially shielded him from increasing attacks from the anti-communists as well as critics within his own party. "All the president is, is a glorified public relations man who spends his time flattering, kissing, and kicking people to get them to do what they are supposed to do anyway." Containment stood as not only the best option for the preservation of democracy across the globe, but for the preservation of Harry Truman and his presidency as well. Still, he recognized that a successful president could not always be popular. "To hell with them. When history is written they will be the sons of bitches -- not I." How right he was.

The Obstinate Opsimath

Despite his relative lack of formal education, Truman remained all his life a keen student of history, and understood all too well that the impact of his decisions could reverberate far beyond his own presidency. Soviet expansionism would have to either be engaged head on with direct force, or slowly and deliberately suffocated with a massive projection of American military muscle, while simultaneously undermining it with substantial foreign aid and unwavering Allied commitment. Yet he never lost sight of the forest for the trees: "We shall never be able to remove suspicion and fear as potential causes of war until communication is permitted to flow, free and open, across international boundaries."

The diminutive senator from Independence, Missouri entered the office of the presidency feeling much too small for the role thrust upon him so abruptly. Hearing of FDR’s sudden death and his own succession to the job, Truman remarked that he felt as if "the sun, the moon, and the stars had fallen on [him]." Yet, he would leave the White House, as Winston Churchill would later express, having done “more than any other man to have saved Western Civilization.”

The incidental presidency of Harry S. Truman was one of immeasurable consequence, and history’s ledger has finally caught up with his uniquely American brand of ordinary exceptionalism. Whatever landed on his desk, the buck truly stopped there.

"It is amazing what you can accomplish if you do not care who gets the credit."